A juried photography contest has disqualified one of the images that was originally picked as a top three finisher in its new AI art category. The reason for the disqualification? The photo was actually taken by a human and not generated by an AI model.

The 1839 Awards launched last year as a way to “honor photography as an art form,” with a panel of experienced judges who work with photos at The New York Times, Christie’s, and Getty Images, among others. The contest rules sought to segregate AI images into their own category as a way to separate out the work of increasingly impressive image generators from “those who use the camera as their artistic medium,” as the 1839 Awards site puts it.

For the non-AI categories, the 1839 Awards rules note that they “reserve the right to request proof of the image not being generated by AI as well as for proof of ownership of the original files.” Apparently, though, the awards did not request any corresponding proof that submissions in the AI category were generated by AI.

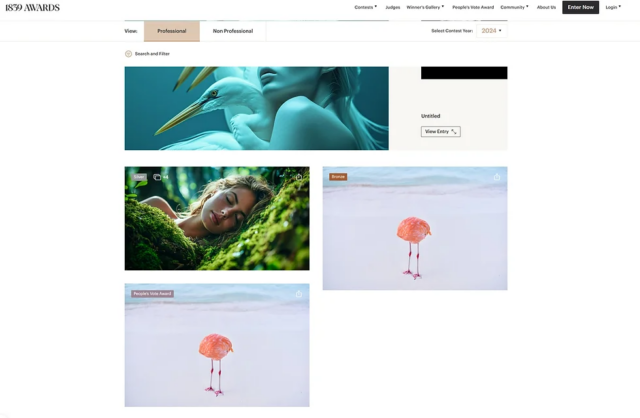

Because of this, photographer Miles Astray was able to enter his photo “F L A M I N G O N E” into that AI-generated category, where it was shortlisted and then picked for third place over plenty of other entries that were not made by a human holding a camera. The photo also won the People’s Choice Award for the AI category after Astray publicly lobbied his social media followers to vote for it multiple times.

Making a statement

On his website, Astray tells the story of a 5 am photo shoot in Aruba where he captured the photo of a flamingo that appears to have lost its head. Astray said he entered the photo in the AI category “to prove that human-made content has not lost its relevance, that Mother Nature and her human interpreters can still beat the machine, and that creativity and emotion are more than just a string of digits.”

That’s not a completely baseless concern. Last year, German artist Boris Eldagsen made headlines after his AI-generated picture “The Electrician” won first prize in the Creative category of the World Photography Organization’s Sony World Photography Award. Eldagsen ended up refusing the prize, writing that he had entered “as a cheeky monkey, to find out if the competitions are prepared for AI images to enter. They are not.”

In a statement provided to press outlets after Astray revealed his deception, the 1839 Awards organizers noted that Astray’s entry was disqualified because it “did not meet the requirements for the AI-generated image category. We understand that was the point, but we don’t want to prevent other artists from their shot at winning in the AI category. We hope this will bring awareness (and a message of hope) to other photographers worried about AI.”

For his part, Astray says his disqualification from the 1839 Awards was “a completely justified and right decision that I expected and support fully.” But he also writes that the work’s initial success at the awards “was not just a win for me but for many creatives out there.”

I’m not sure I buy that interpretation, though. Art isn’t like chess, where the brute force of machine learning efficiency has made even the best human players relatively helpless. Instead, as conceptual artist Danielle Baskin told Ars when talking about the DALL-E image generator, “all modern AI art has converged on kind of looking like a similar style, [so] my optimistic speculation is that people are hiring way more human artists now.”

The whole situation brings to mind the ostensibly AI-generated George Carlin-style comedy special released earlier this year, which the creators later admitted was written entirely by a human. At the time, I noted how our views of works of art are immediately colored as soon as the “AI generated” label is applied. Maybe you grade the work on a bit of a curve (“Well, it’s not bad for a machine“), or maybe you judge it more harshly for its artificial creation (“It obviously doesn’t have the human touch“).

In any case, reactions to AI artwork are “a reflection of all the fear and promise inherent in computers continuing to encroach on areas we recently thought were exclusively ‘human,’ as well as the economic and philosophical impacts of that trend,” as I wrote when talking about the fake AI Carlin. And those human-centric biases mean we can’t help but use a different eye to judge works of art presented as AI creations.

Entering a human photograph into an AI-generated photo contest says more about how we can exploit those biases than it does about the inherent superiority of man or machine in a field as subjective as art. This isn’t John Henry bravely standing up to a steam engine, it’s Homer Simpson winning a nuclear plant design contest that was not intended for him.