As far as black holes go, there are two categories: supermassive ones that live at the center of the galaxies (and we’re unsure about how they got there) and stellar mass ones that formed through the supernovae that end the lives of massive stars.

Prior to the advent of gravitational wave detectors, the heaviest stellar-mass black hole we knew about was only a bit more than a dozen times the mass of the Sun. And this makes sense, given that the violence of the supernova explosions that form these black holes ensures that only a fraction of the dying star’s mass gets transferred into its dark offspring. But then the gravitational wave data started flowing in, and we discovered there were lots of heavier black holes, with masses dozens of times that of the Sun. But we could only find them when they smacked into another black hole.

Now, thanks to the Gaia mission, we have observational evidence of the largest black hole in the Milky Way outside of the supermassive one, with a mass 33 times that of the Sun. And, in galactic terms, it’s right next door at about 2,000 light-years distant, meaning it will be relatively easy to learn more.

Mapping the stars

Although stellar-mass black holes are several times the mass of the Sun, they aren’t really all that heavy in the grand scheme of things. The sorts of stars that tend to leave black holes behind also tend to lead violent existences, spewing a lot of themselves into space before dying. And the supernova that forms the black hole obviously expels a lot of the star’s mass, rather than feeding it into the black hole. It had been thought that these processes set limits on how big a stellar mass black hole could be when it forms.

The discovery of larger black holes through gravitational wave detectors suggested that this wasn’t true. While there are ways for black holes to get bigger after they form—excessive feeding, mergers—it wasn’t clear that these events occurred often enough to explain the frequency of heavy black holes that we were seeing. And detecting them via gravitational waves doesn’t tell us anything about the history of how they got that large.

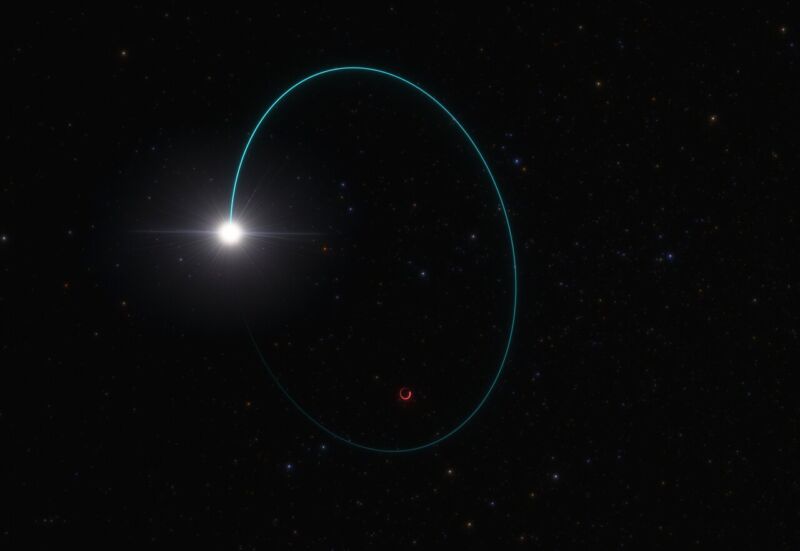

Which is why the discovery of Gaia BH3 (which is what the research team is using to avoid having to retype Gaia DR3 4318465066420528000 all the time) is so intriguing. The black hole is sitting calmly in a binary system, not doing anything in particular. But we know it’s there due to its gravitational influence.

Gaia is an ESA mission to map the location and movement of many of the Milky Way’s brighter stars by imaging them multiple times from different perspectives. It also gathers basic data on the stars’ light, allowing us to estimate things like age and composition. And, in addition to their movement across the galaxy, Gaia can measure their movement relative to Earth, a method that is useful for the detection of orbital interactions, such as the presence of companion stars or exoplanets.

The Gaia team was busy preparing for the fourth release of the data from the spacecraft and were running validation tests on the software used to detect binary star systems when they stumbled across Gaia BH3. While normally they’d publish its discovery at the same time as the data release, they consider the new object too important to wait: “We took the exceptional step of the publication of this paper based on preliminary data ahead of the official DR4 due to the unique nature of the discovery, which we believe should not be kept from the scientific community until the next release.”

Finding the invisible

Every star in our galaxy is in motion relative to every other. They orbit the center of our galaxy and may have a history that has imparted additional momentum—gravitational interactions with neighbors, having been part of a smaller galaxy that was consumed by the Milky Way, and so on. But that motion only changes on very long time scales. By contrast, any star in an orbit experiences regular changes in its motion in addition to its overall travel through the galaxy. As part of processing its data, the Gaia team attempts to identify both overall motion and any indications that a star is orbiting as part of a binary system.

The star that is orbiting Gaia BH3 is similar in mass to the Sun but shows the sort of periodic wobbles that indicate it’s in a mutual orbit with a companion. The companion itself, however, was completely invisible, which means it is almost certainly a black hole (the Gaia data had already been used to identify black holes this way). And, based on the mass and orbital motion of the visible star, it’s possible to estimate the mass of the invisible companion.

The estimate ended up being 32 solar masses, which is significantly larger than anything else identified in the Gaia dataset. So, the Gaia team wanted to confirm this wasn’t a software issue and used Earth-based telescopes to observe the same system. Three different observatories confirmed it was there, and the resulting mass estimates were slightly larger than those derived from the Gaia data alone: just under 33 solar masses.

Assuming it’s a single object and not two black holes orbiting each other closely, that makes it the largest non-supermassive black hole known in the Milky Way. And it places it in the mass range that had been difficult to explain via formations in supernovae.