Phoenix Public Library

John Milton is widely considered to be one of the greatest English poets who ever lived—just ask such luminaries as John Dryden, Alexander Pope, Samuel Jonson, and Voltaire, who once declared, “Milton remains the glory and the wonder of England.” But while Milton’s own books continue to be widely read and studied, there are only a handful of books in collections today known to have been part of his personal library.

Add one more title to that small list, as scholars recently discovered a copy of Holinshed’s Chronicles of England, Scotland, and Ireland in the Phoenix Public Library, containing handwritten notes in Milton’s distinctive hand. This makes the volume extra-special, since only two other books once owned by Milton also contain handwritten notes. The scholars detailed their findings in a new article published in the Times Literary Supplement.

Holinshed’s Chronicles is a hugely influential and comprehensive three-volume history of Great Britain, first published in 1577; it was followed by a second edition in 1587. A London printer named Reginald Wolfe started the project and hired Raphael Holinshed and William Harrison to help him create a “universal cosmography of the whole world.” Wolfe died before the book could be completed, and the project was eventually scaled down to a history of England, Scotland, and Ireland, complete with maps and illustrations.

The Chronicles is perhaps best known today as the primary source for William Shakespeare’s history plays, as well as Macbeth and parts of King Lear and Cymbeline. But plenty of other writers found it to be a useful resource, including Edmund Spenser, Shakespeare’s contemporary, Christopher Marlow, and John Milton. Milton is best known for his epic poem Paradise Lost, but he also wrote many other poems and prose; references to Holinshed’s Chronicles abound in the latter, including Of Reformation (1641), The History of Britain (1670), and Milton’s commonplace book (essentially a personal journal).

Phoenix Public Library

Real estate magnate and philanthropist Alfred Knight purchased an 1857 edition of Holinshed in 1942 from Beverly Hills, California, bookseller Maxwell Huntley for $38.60—including shipping to Phoenix, where Knight lived. It was added to Knight’s extensive rare book collection particularly focused on what the authors of the TLS article term “Shakespeareana.” Knight also owned a first edition of Paradise Lost and a 1697 first edition of Milton’s collected prose. He bequeathed his collection to the people of Phoenix under the care of the public library.

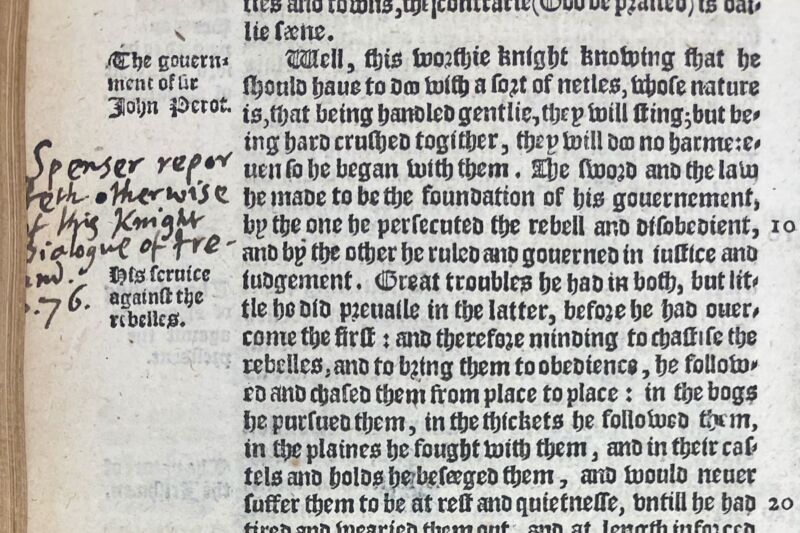

In March, Arizona State University hosted a forum at the library, and custodians brought out the Holinshed—consisting of two bound tomes incorporating the original three volumes—so those in attendance could examine it. Aaron Pratt of the University of Texas was among the attendees and noticed that an “e'” in handwritten notes in the margins seemed familiar. “I was like, ‘God, there’s no way in hell this is true, but it kind of looks like this stupid way Milton writes ‘e,’” Pratt said. Early on, Milton used the letter epsilon for his e’s (ε), but sometime in the late 1630s, he switched to using an italic e.

Naturally, Pratt was intrigued and examined the handwritten marginalia more closely, finding “scratchy brackets” with notations that looked very much like ones known to be written by Milton in a Shakespeare First Folio discovered in the Philadelphia Free Library in 2019. He and co-author Claire Bourne of Penn State, who was also in attendance, excitedly began comparing the annotations in the Holinshed and the folio.

Bourne then texted photographs of the handwriting to co-author Jason Scott-Warren, director of the Cambridge Center for Material Texts in England. Scott-Warren was the one who had verified Milton’s handwriting in the Shakespeare folio in 2019. Known to be conservative in his assessments, Scott-Warren compared the handwritten Holinshed notes to Milton’s handwriting in two of the poet’s handwritten manuscripts. He confirmed that the Holinshed handwriting was indeed Milton’s with an exclamatory, “Wow. Bingo!”

![Raphael Holinshed's lewd anecdote about the mother of William the Conqueror, Arlete. Milton crossed out the passage with a diagonal line and added a note: "an unbecom[ing] / tale for a hist[ory] / and as pedlerl[y] / expresst."](https://cdn.arstechnica.net/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/milton1-640x853.jpg)

Phoenix Public Library

In addition to the italic e, the Holinshed notations contain the poet’s distinctive hooks and curls on certain letters, as well as his unevenness in forming lowercase s’s. Textual analysis between the marked Holinshed passages and Milton’s Commonplace Book also indicates the poet owned this particular copy. More than 90 percent of references to Holinshed correspond to marked passages in the Knight Collection copy of the second bound volume. And several of the handwritten notes in the latter cite other books scholars know were once part of Milton’s personal library.

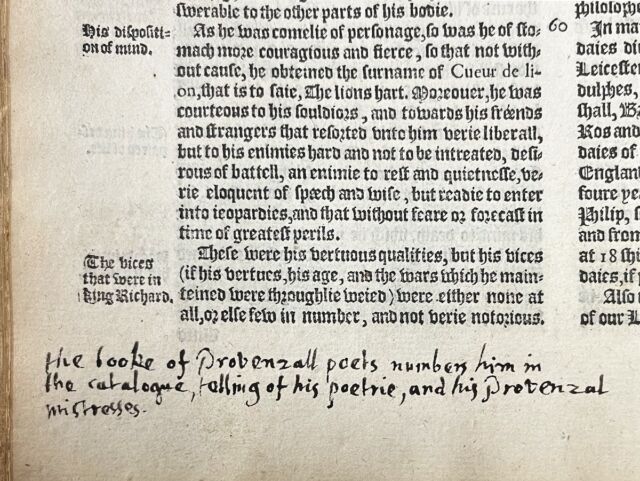

Of particular interest is where Milton crossed out a particularly racy passage about the mother of William the Conqueror, Arlete (Herleva), mistress of Duke Robert I of Normandy. The anecdote describes how the duke noticed Arlete dancing and brought her to bed, whereupon she tore her dress rather than allow him to lift it himself because “it would be immodest for her ‘dependant’ garments to be ‘mountant’ to the duke’s mouth.” Milton added a note decrying the anecdote as “an unbecom[ing]/ tale for a hist[ory],” in a style more fitting to peddling wares on the street. “Milton is renowned as an enemy of press censorship, but here we see he was not immune to prudishness,” said Scott-Warren.

As for the provenance of this copy of Holinshed, the authors note that most of Milton’s personal books were sold in batches around the time he died in 1674, but there’s no record of the Holinshed for over a century. The volumes were rebound in red leather with marbled endpapers around 1800, and historian and collector William Maskell signed the book and made his own notes starting around 1847. While most of Maskell’s books were sold at various auctions, it seems the Holinshed remained in the family’s private collection until it showed up in Beverly Hills in 1942.