Qualcomm

Signs point to Qualcomm’s Snapdragon X Elite processors showing up in actual, real-world, human-purchasable computers in the next couple of months after years of speculation and another year or so of hype.

For those who haven’t been following along, this will allegedly be Qualcomm’s first Arm processor for Windows PCs that does for PCs what Apple’s M-series chips did for Macs, promising both better battery life and better performance than equivalent Intel chips. This would be a departure from past Snapdragon chips for PCs, which have performed worse than (or, at best, similarly to) existing Intel options, barely improved battery life, and come with a bunch of software incompatibility problems to boot.

Early benchmarks that have trickled out look promising for the Snapdragon X. And there are other reasons to be optimistic—the Snapdragon X Elite’s design team is headed up by some of the same people who made Apple Silicon so successful in the first place.

Rumors indicate that Microsoft’s flagship Surface tablet this year will switch to using Qualcomm’s Arm chips exclusively rather than selling Arm and Intel versions alongside each other (an Intel Surface Pro 10 exists, but it’s only sold to businesses). Microsoft has tried to make Arm Windows happen a bunch of times. But this time feels different.

A brief history of Arm Windows

The first public version of Windows to run on Arm processors was Windows RT, an Arm-compatible offshoot of Windows 8 that launched on a bare handful of devices back in late 2012.

Windows RT came with significant limitations, most notably a total inability to run traditional x86 Windows desktop apps—all apps had to come from the Microsoft Store, which was considerably more barren than it is today. There was no x86 compatibility mode at all.

That limitation may have been due in part to the limited, low-performance Arm hardware available at the time. Arm processors were still predominantly 32-bits, with slow processors and GPUs, 32 or 64GB of slow flash storage, and just 2GB of memory (at the time, 4GB was generally considered adequate for a PC, and 8GB was roomy). Even if you did have x86 app translation, translated apps would have felt awful since the Arm hardware already struggled to run the native built-in apps consistently well.

Andrew Cunningham

Windows RT died the death it deserved to die; it never ran on many devices, and those that did had totally vanished from the market by 2015 or so. But the technical underpinnings of the operating system remain relevant today.

As detailed by then-Windows head Steven Sinofsky, Microsoft did significant work to define a hardware abstraction layer (HAL), ACPI firmware, and basic class drivers for the Arm version of Windows so that the OS could install and run as expected on a wide variety of barely standardized Arm hardware the same way it did on a thoroughly standardized x86 PC. (Compare this to Google’s Wild West approach to Android, which to this day can’t install basic OS or security updates without specific intervention from chipmakers and device manufacturers).

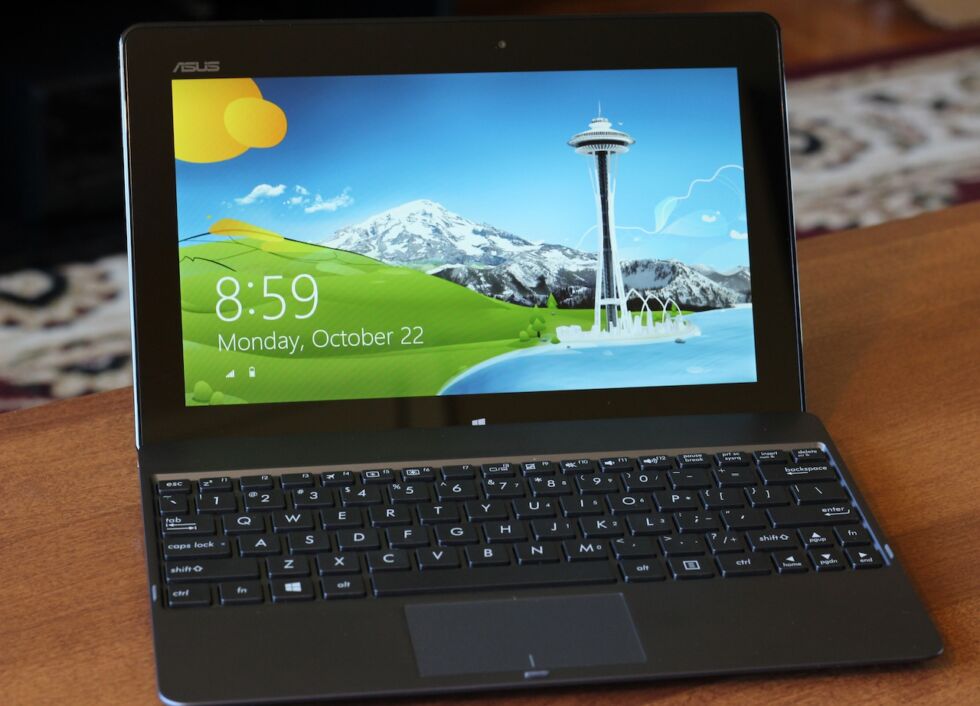

These were building blocks Microsoft could re-use for Windows 10, which first came to Arm devices in 2017 with support for 32-bit x86 app translation. This version of Windows-on-Arm also functioned more as a technical demo than the dawn of a new era, but it did come closer to becoming what Windows-on-Arm needed to be to succeed: a drop-in replacement for the x86 version of Windows, where the two versions were largely indistinguishable for non-technical users.

The next big step down that path came in 2020 when Microsoft announced a preview of 64-bit Intel app translation for Arm PCs, though the final version ended up being exclusive to Windows 11 when it launched in late 2021 (leaving behind, incidentally, that first wave of Windows 10 Arm PCs with a Snapdragon 835 processor in them—another case where early-adopting into this ecosystem has hosed users. Developers also got an easier on-ramp to Arm when Microsoft began allowing them to mix x86 and Arm code in the same app.

That brings us to where we are now: an Arm version of Windows that still has some compatibility gaps, especially around external accessories and specialized software. But the vast majority of productivity apps and even games will now run happily on the Arm version of Windows, with no user or developer intervention required.