University of New South Wales, Sydney

Diehard fans of cold-brew coffee put in a lot of time and effort for their preferred caffeinated beverage. But engineers at the University of New South Wales, Sydney, figured out a nifty hack. They rejiggered an existing espresso machine to accommodate an ultrasonic transducer to administer ultrasonic pulses, thereby reducing the brewing time from 12 to 24 hours to just under three minutes, according to a new paper published in the journal Ultrasonics Sonochemistry.

As previously reported, rather than pouring boiling or near-boiling water over coffee grounds and steeping for a few minutes, the cold-brew method involves mixing coffee grounds with room-temperature water and letting the mixture steep for anywhere from several hours to two days. Then it is strained through a sieve to filter out all the sludge-like solids, followed by filtering. This can be done at home in a Mason jar, or you can get fancy and use a French press or a more elaborate Toddy system. It’s not necessarily served cold (although it can be)—just brewed cold.

The result is coffee that tastes less bitter than traditionally brewed coffee. “There’s nothing like it,” co-author Francisco Trujillo of UNSW Sydney told New Scientist. “The flavor is nice, the aroma is nice and the mouthfeel is more viscous and there’s less bitterness than a regular espresso shot. And it has a level of acidity that people seem to like. It’s now my favorite way to drink coffee.”

While there have been plenty of scientific studies delving into the chemistry of coffee, only a handful have focused specifically on cold-brew coffee. For instance, a 2018 study by scientists at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia involved measuring levels of acidity and antioxidants in batches of cold- and hot-brew coffee. But those experiments only used lightly roasted coffee beans. The degree of roasting (temperature) makes a significant difference when it comes to hot-brew coffee. Might the same be true for cold-brew coffee?

To find out, the same team decided in 2020 to explore the extraction yields of light-, medium-, and dark-roast coffee beans during the cold-brew process. They used the cold-brew recipe from The New York Times for their experiments, with a water-to-coffee ratio of 10:1 for both cold- and hot-brew batches. (Hot brew normally has a water-to-coffee ratio of 20:1, but the team wanted to control variables as much as possible.) They carefully controlled when water was added to the coffee grounds, how long to shake (or stir) the solution, and how best to press the cold-brew coffee.

The team found that for the lighter roasts, caffeine content and antioxidant levels were roughly the same in both the hot- and cold-brew batches. However, there were significant differences between the two methods when medium- and dark-roast coffee beans were used. Specifically, the hot-brew method extracts more antioxidants from the grind; the darker the bean, the greater the difference. Both hot- and cold-brew batches become less acidic the darker the roast.

UNSW/Francisco Trujillo

That gives cold brew fans a few handy tips, but the process remains incredibly time-consuming; only true aficionados have the patience required to cold brew their own morning cuppa. Many coffee houses now offer cold brews, but it requires expensive, large semi-industrial brewing units and a good deal of refrigeration space. According to Trujillo, the inspiration for using ultrasound to speed up the process arose from failed research attempts to extract more antioxidants. Those experiments ultimately failed, but the setup produced very good coffee.

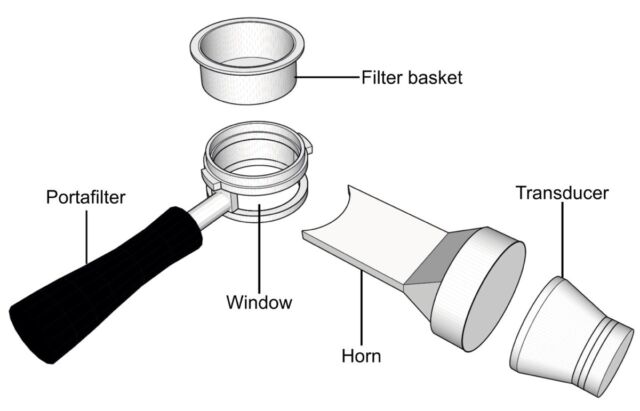

Trujillo et al. used a Breville Dual Boiler BES920 espresso machine for their latest experiments, with a few key modifications. They connected a bolt-clawed transducer to the brewing basket with a metal horn. They then used the transducer to inject 38.8 kHz sound waves through the walls at several different points, thereby transforming the filter basket into a powerful ultrasonic reactor.

The team used the machine’s original boiler but set it up to be independently controlled it with an integrated circuit to better manage the temperature of the water. As for the coffee beans, they picked Campos Coffee’s Caramel & Rich Blend (a medium roast). “This blend combines fresh, high-quality specialty coffee beans from Ethiopia, Kenya, and Colombia, and the roasted beans deliver sweet caramel, butterscotch, and milk chocolate flavors,” the authors wrote.

There were three types of samples for the experiments: cold brew hit with ultrasound at room temperature for one minute or for three minutes, and cold brew prepared with the usual 24-hour process. For the ultrasonic brews, the beans were ground into a fine grind typical for espresso, while a slightly coarser grind was used for the traditional cold-brew coffee.