E. T. H. Teague

A team of Japanese and Belgian astronomers has re-examined the sunspot drawings made by 17th century astronomer Johannes Kepler with modern analytical techniques. By doing so, they resolved a long-standing mystery about solar cycles during that period, according to a recent paper published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Precisely who first observed sunspots was a matter of heated debate in the early 17th century. We now know that ancient Chinese astronomers between 364 and 28 BCE observed these features and included them in their official records. A Benedictine monk in 807 thought he’d observed Mercury passing in front of the Sun when, in reality, he had witnessed a sunspot; similar mistaken interpretations were also common in the 12th century. (An English monk made the first known drawings of sunspots in December 1128.)

English astronomer Thomas Harriot made the first telescope observations of sunspots in late 1610 and recorded them in his notebooks, as did Galileo around the same time, although the latter did not publish a scientific paper on sunspots (accompanied by sketches) until 1613. Galileo also argued that the spots were not, as some believed, solar satellites but more like clouds in the atmosphere or the surface of the Sun. But he was not the first to suggest this; that credit belongs to Dutch astronomer Johannes Fabricus, who published his scientific treatise on sunspots in 1611.

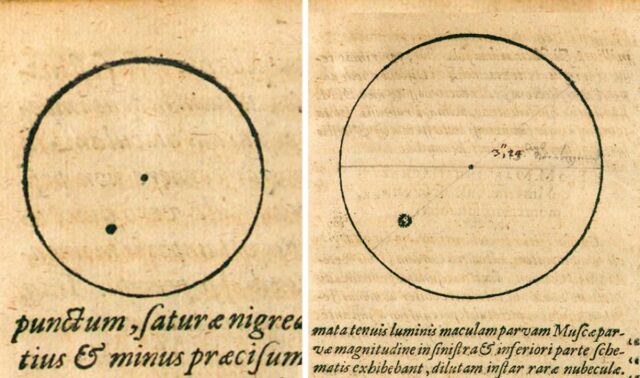

Kepler read that particular treatise and admired it, having made his sunspot observations using a camera obscura in 1607 (published in a 1609 treatise), which he initially thought was a transit of Mercury. He retracted that report in 1618, concluding that he had actually seen a group of sunspots. Kepler made his solar drawings based on observations conducted both in his own house and in the workshop of court mechanic Justus Burgi in Prague. In the first case, he reported “a small spot in the size of a small fly”; in the second, “a small spot of deep darkness toward the center… in size and appearance like a thin flea.”

Public domain

The long-standing debate that is the subject of this latest paper concerns the period from around 1645 to 1715, during which there were very few recorded observations of sunspots despite the best efforts of astronomers. This was a unique event in astronomical history. Despite only observing some 59 sunspots during this time—compared to between 40,000 to 50,000 sunspots over a similar time span in our current age—astronomers were nonetheless able to determine that sunspots seemed to occur in 11-year cycles.

German astronomer Gustav Spörer noted the steep decline in 1887 and 1889 papers, and his British colleagues, Edward and Annie Maunder, expanded on that work to study how the latitudes of sunspots changed over time. That period became known as the “Maunder Minimum.” Spörer also came up with “Spörer’s law,” which holds that spots at the start of a cycle appear at higher latitudes in the Sun’s northern hemisphere, moving to successively lower latitudes in the southern hemisphere as the cycle runs its course until a new cycle of sunspots begins in the higher latitudes.

But precisely how the solar cycle transitioned to the Maunder Minimum has been far from clear. Reconstructions based on tree rings have produced conflicting data. For instance, one such reconstruction concluded that the gradual transition was preceded either by an extremely short solar cycle of about five years or an extremely long solar cycle of about 16 years. Another tree ring reconstruction concluded the solar cycle would have been of normal 11-year duration.

Independent observational records can help resolve the discrepancy. That’s why Hisashi Hayakawa of Nagoya University in Japan and co-authors turned to Kepler’s drawings of sunspots for additional insight, which predate existing telescopic observations by several years.