Aurich Lawson

Know your enemy, know yourself. It’s a centuries-old strategy. But even in the present-day war against cancer, achieving it remains elusive. In many cases, cancer cells blend in with healthy ones. They bear no unique molecular markers or targets that we can aim clinical defenses at. That means any deadly strike on enemy cancer cells could result in casualties among healthy ones as well. The untenable toxicity of this artless warfare has led some researchers to rethink the ancient script—and flip it: know yourself, know your enemy.

In a set of clever and highly technical tricks, researchers are working on ways to precisely mark and shield healthy cells from chemical weapons, abandoning the effort to pick out enemy cancer cells specifically. By exploiting molecular markers common among many types of cells, researchers can safeguard healthy cells, leaving only the cancer cells in harm’s way.

A drug or therapy that targets common markers would normally lay waste to cancerous and healthy cells alike. But that’s not the case in this radical approach, which is first being used to treat blood cancers. For the strategy, researchers collect healthy blood stem cells and genetically engineer tiny, benign changes to a common molecular marker on them. Those tiny changes make the healthy cells essentially invisible to killer treatments. After the engineered cells are transplanted into a patient, clinicians can deploy the treatments. The cancerous cells that lack the genetic tweak are now easily killed by the drug or therapy, while the healthy engineered cells are left untouched.

The utility of the tactic doesn’t end there. While cloaking healthy cells means researchers no longer need to know their specific enemy from healthy cells with precision, that imprecision opens vast possibilities. For one, it has the potential to create a virtually universal treatment for blood cancers. Whatever specific type of cancer is present, targeting a ubiquitous marker on blood cells and cloaking healthy cells will eradicate whatever strain of cancer is lurking among them.

“We no longer have to worry whether a tumor originated from a B cell or from a T cell or from a myeloid cell. It doesn’t matter,” transplantation immunologist Lukas Jeker of the University of Basel in Switzerland told Ars. “As long as it is a blood cell, we can use [the strategy], and that’s why we think it’s going to be almost universal.”

For now, the results are still in the pre-clinical realm—mouse studies and Petri dishes—but researchers are swiftly marching toward clinical trials with compelling results in hand. Those trials using the strategy “are eagerly anticipated by the scientific and medical community,” oncologist Miriam Kim of the Washington University School of Medicine wrote in Trends in Cancer in December. Those trials are now expected in the next few years.

A universal target

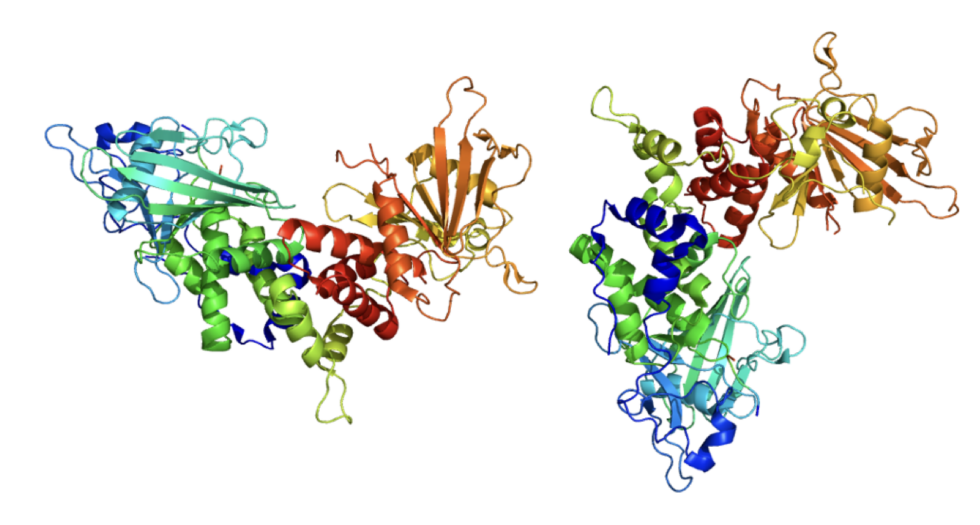

Last month, Jeker and his colleagues published the early results of their nearly universal strategy. It targets CD45, a molecular marker found only on blood cells, with the exceptions of red blood cells and platelets. It’s called a pan-hematopoietic marker. In the study published in Nature, the researchers successfully used a potent treatment that kills anything with an unaltered CD45. The treatment is an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC). The antibody part of the ADC is a protein that can uniquely latch onto CD45 and, once attached, deliver a toxic payload bound to it, which contains an existing cell-killing drug. Normally, a CD45-targeting ADC would wipe out the entire hematopoietic cell population. But with healthy blood stem cells shielded by a tweak to their CD45, the ADC selectively kills off the unprotected and cancerous cells.

In mouse experiments, the strategy worked. “It was just unbelievably effective. I mean, the first time I saw the results, I didn’t believe it. I thought something must be wrong,” Jeker said.

First, the researchers injected mice with four different cancerous cell lines. After a single dose of the CD45-targeting ADC, all the rodents’ tumors shrank rapidly. They then tested it out with a cancer patient’s cells. The patient had a type of blood cancer called AML, Acute Myeloid Leukemia, which is a kind of blood cancer that originates in the bone marrow. The researchers transplanted the patient’s AML cells into mice that had already gotten a transplant of healthy CD45-shielded blood stem cells. They then treated the mice with their CD45-targeting ADC.

“The results were really just black or white. It’s just like, it just works,” Jeker said. The CD45-shielded cells were protected. The researchers saw no evidence of them being killed. Meanwhile, the patient’s AML cells were eradicated. “So we really get the dream result,” Jeker said. “We have the complete protection, and we get complete elimination of the disease, which is what we want, ultimately.”