Tony C. French/Getty

In the urgent quest for a more sustainable global food system, livestock are a mixed blessing. On the one hand, by converting fibrous plants that people can’t eat into protein-rich meat and milk, grazing animals like cows and sheep are an important source of human food. And for many of the world’s poorest, raising a cow or two—or a few sheep or goats—can be a key source of wealth.

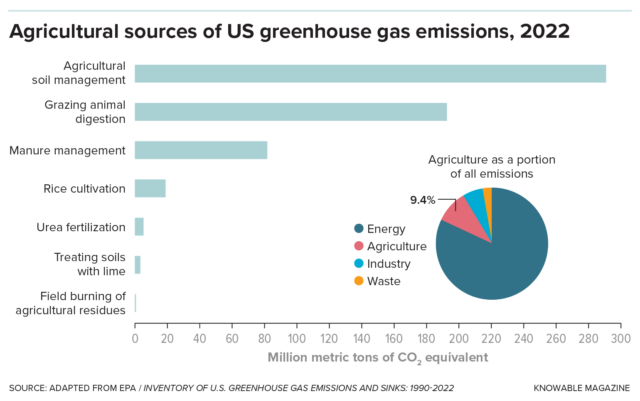

But those benefits come with an immense environmental cost. A study in 2013 showed that globally, livestock account for about 14.5 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, more than all the world’s cars and trucks combined. And about 40 percent of livestock’s global warming potential comes in the form of methane, a potent greenhouse gas formed as they digest their fibrous diet.

That dilemma is driving an intense research effort to reduce methane emissions from grazers. Existing approaches, including improved animal husbandry practices and recently developed feed additives, can help, but not at the scale needed to make a significant global impact. So scientists are investigating other potential solutions, such as breeding low-methane livestock and tinkering with the microbes that produce the methane in grazing animals’ stomachs. While much more research is needed before those approaches come to fruition, they could be relatively easy to implement widely and could eventually have a considerable impact.

Knowable Magazine

The good news—and an important reason to prioritize the effort—is that methane is a relatively short-lived greenhouse gas. Whereas the carbon dioxide emitted today will linger in the atmosphere for more than a century, today’s methane will wash out in little more than a decade. So tackling methane emissions now can lower greenhouse gas levels and thus help slow climate change almost immediately.

“Reducing methane in the next 20 years is about the only thing we have to keep global warming in check,” says Claudia Arndt, a dairy nutritionist working on methane emissions at the International Livestock Research Institute in Nairobi, Kenya.

The methane dilemma

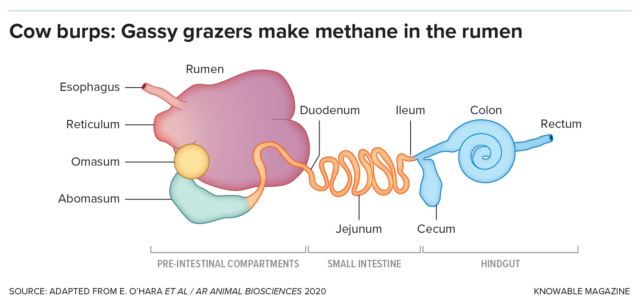

The big challenge in lowering methane is that the gas is a natural byproduct of what makes grazing animals uniquely valuable: their partnership with a host of microbes. These microbes live within the rumen, the largest of the animals’ four stomachs, where they break down the fibrous food into smaller molecules that the animals can absorb for nutrition. In the process, they generate large amounts of hydrogen gas, which is converted into methane by another group of microbes called methanogens.

Knowable Magazine

Most of this methane, often referred to as enteric methane, is belched or exhaled out by the animals into the atmosphere—just one cow belches out around 220 pounds of methane gas per year, for example. (Contrary to popular belief, very little methane is expelled in the form of farts. Piles of manure that accumulate in feedlots and dairy barns account for about a quarter of US livestock methane, but aerating the piles or capturing the methane for biogas can prevent those emissions; the isolated cow plops from pastured grazing animals generate little methane.)