Esper, Torbenson, and Büntgen

Starting in June of last year, global temperatures went from very hot to extreme. Every single month since June, the globe has experienced the hottest temperatures for that month on record—that’s 11 months in a row now, enough to ensure that 2023 was the hottest year on record, and 2024 will likely be similarly extreme.

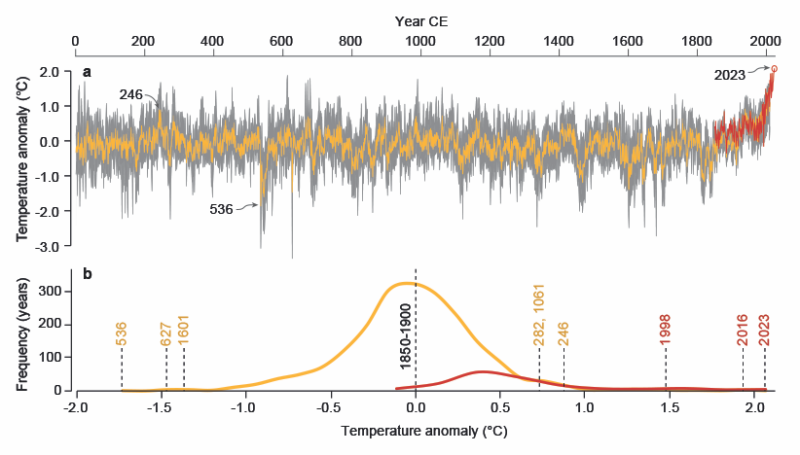

There’s been nothing like this in the temperature record, and it acts as an unmistakable indication of human-driven warming. But how unusual is that warming compared to what nature has thrown at us in the past? While it’s not possible to provide a comprehensive answer to that question, three European researchers (Jan Esper, Max Torbenson, and Ulf Büntgen) have provided a partial answer: the Northern Hemisphere hasn’t seen anything like this in over 2,000 years.

Tracking past temperatures

Current temperature records are based on a global network of data-gathering hardware. But, as you move back in time, gaps in that network go from rare to ever more common. Moving backward from 1900, the network shrinks to just a few dozen land-based thermometers, almost all of them in Europe.

That doesn’t mean we have no idea what temperatures were like prior to 1850, however. A variety of what are called proxies have been developed: processes that leave a physical record that’s affected by the temperature. These include things like the size of annual tree rings or the ratio of oxygen isotopes found in ice. It’s possible to take proxies from multiple locations and generate estimates of global and regional temperatures before the instrument record.

If you line the two up, it’s easy to see that recent warming has been exceptional compared to any trends seen since the end of the last ice age.

But proxy records are somewhat inexact; depending on the proxy, they may not fully capture extreme changes and may average out year-to-year swings in temperatures. So, it’s possible that a few exceptionally hot years occurred in the past, but we have been unable to detect their presence in the proxy records because they were surrounded by relatively cool years.

All of this makes it difficult to say how much of an outlier 2023 was for the planet. Esper, Torbenson, and Büntgen decided to try to find out the best they could, by limiting themselves to areas of the globe where we have the best data. As mentioned above, for the temperature record, that means the Northern Hemisphere, more specifically the region above 30° north—think anything north of Egypt, New Orleans, or the southernmost part of the main Japanese islands. We’ve also got good proxy records of that area based on tree ring data, which captures a record of summertime temperatures. These include some individually long-lived trees, allowing for a very extensive record.

Comparing extremes

The first thing the three researchers did was try to align the temperature record with the proxy record. If you simply compare temperatures within the instrument record, 2023 summer temperatures were just slightly more than 2°C higher than the 1850–1900 temperature records. But, as mentioned, the record for those years is a bit sparse. A comparison with proxy records of the 1850–1900 period showed that the early instrument record ran a bit warm compared to a wider sampling of the Northern Hemisphere. Adjusting for this bias revealed that the summer of 2023 was about 2.3° C above pre-industrial temperatures from this period.

But the proxy data from the longest tree ring records can take temperatures back over 2,000 years to year 1 CE. Compared to that longer record, summer of 2023 was 2.2° C warmer (which suggests that the early instrument record runs a bit warm).

So, was the summer of 2023 extreme compared to that record? The answer is very clearly yes. Even the warmest summer in the proxy record, CE 246, was only 0.97° C above the 2,000-year average, meaning it was about 1.2° C cooler than 2023. The coldest summer in the proxies was 536 CE, which came in the wake of a major volcanic eruption. That was roughly 4° C cooler than 2023.

While the proxy records have uncertainties, those uncertainties are nowhere near large enough to encompass 2023. Even if you take the maximum temperature with the 95 percent confidence range of the proxies, the summer of 2023 was more than half a degree warmer.

Obviously, this analysis is limited to comparing a portion of one year to centuries of proxies, as well as limited to one area of the globe. It doesn’t tell us how much of an outlier the rest of 2023 was or whether its extreme nature was global.

But the work done by Esper, Torbenson, and Büntgen was likely just the first of its kind. We’re now closing in on a full year of data that shows that extreme temperatures are both global and extended well beyond the summer. And that should enable the consideration of additional proxies that don’t rely on tree rings, and are therefore sensitive to temperatures outside the summer.

In other words, the new paper is a solid early analysis of an event that’s ongoing. With a bit more time, we’ll start to get a better perspective on just how exceptional recent greenhouse warming has been.

Nature, 2024. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07512-y (About DOIs).

Listing image by Daniel Garrido