United Launch Alliance

It has been nearly four years since the US Air Force made its selections for companies to launch military payloads during the mid-2020s. The military chose United Launch Alliance, and its Vulcan rocket, to launch 60 percent of these missions; and it chose SpaceX, with the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy boosters, to launch 40 percent.

Although the large Vulcan rocket was still in development at the time, it was expected to take flight within the next year or so. Upon making the award, an Air Force official said the military believed Vulcan would soon be ready to take flight. United Launch Alliance was developing the Vulcan rocket in order to no longer be reliant on RD-180 engines that are built in Russia and used by its Atlas V rocket.

“I am very confident with the selection that we have made today,” William Roper, assistant secretary of the Air Force for acquisition, technology, and logistics, said at the time. “We have a very low-risk path to get off the RD-180 engines.”

As part of the announcement, Roper disclosed the first two missions that would fly on Vulcan. The USSF-51 mission was scheduled for launch in the first quarter of 2022, and the USSF-106 mission was scheduled for launch in the third quarter of 2022.

“I am growing concerned”

It turned out to not be such a low-risk path. The Vulcan rocket’s development, of course, has since been delayed. It did not make its debut in 2020 or 2021 and only finally took flight in January of this year. The mission was completely successful—an impressive feat for a new rocket with new engines—but United Launch Alliance still must complete a second flight before the US military certifies Vulcan for its payloads.

Due to these delays, the USSF-51 mission was ultimately moved off of Vulcan and onto an Atlas V rocket. It is scheduled to launch no earlier than next month. The USSF-106 mission remains manifested on a Vulcan as that rocket’s first national security mission, but its launch date is uncertain.

For several years there have been rumblings about Air Force and Space Force officials being unhappy with the delays by United Launch Alliance, as well as with Blue Origin, which is building the BE-4 rocket engines that power Vulcan’s first stage. However, these concerns have rarely broken into public view.

That changed Monday when The Washington Post reported on a letter from Air Force Assistant Secretary Frank Calvelli to the co-owners of United Launch Alliance, Boeing, and Lockheed Martin. In the letter sent on May 10, a copy of which was obtained by Ars, Calvelli urges the two large aerospace contractors to get moving on certification and production of the Vulcan rocket.

“I am growing concerned with ULA’s ability to scale manufacturing of its Vulcan rocket and scale its launch cadence to meet our needs,” Calvelli wrote. “Currently there is military satellite capability sitting on the ground due to Vulcan delays. ULA has a backlog of 25 National Security Space Launch (NSSL) Phase 2 Vulcan launches on contract.”

These 25 launches, Calvelli notes, are due to be completed by the end of 2027. He asked Boeing and Lockheed to complete an “independent review” of United Launch Alliance’s ability to scale manufacturing of its Vulcan rockets and meet its commitments to the military. Calvelli also noted that Vulcan has made commitments to launch dozens of satellites for others over that period, a reference to a contract between United Launch Alliance and Amazon for Project Kuiper satellites.

It’s difficult to scale

Calvelli’s letter comes at a dynamic moment for United Launch Alliance. This week the company is set to launch the most critical mission in its 20-year history: two astronauts flying inside Boeing’s Starliner spacecraft. This mission may take place as early as Friday evening from Florida on an Atlas V vehicle.

In addition, the company is for sale. Ars reported in February that Blue Origin, which is owned by Jeff Bezos, is the leading candidate to buy United Launch Alliance. It is plausible that Calvelli’s letter was written with the intent of signaling to a buyer that the government would not object to a sale in the best interests of furthering Vulcan’s development.

But the message here is unequivocally that the government wants United Launch Alliance to remain competitive and get Vulcan flying safely and frequently.

That may be easier said than done. Vulcan’s second certification mission was supposed to be the launch of the Dream Chaser spacecraft this summer. However, as Ars reported last month, that mission will no longer fly before at least September, if not later, because the spacecraft is not ready for its debut. As a result, Space News reported on Monday that United Launch Alliance is increasingly likely to fly a mass simulator on the rocket’s second flight later this year.

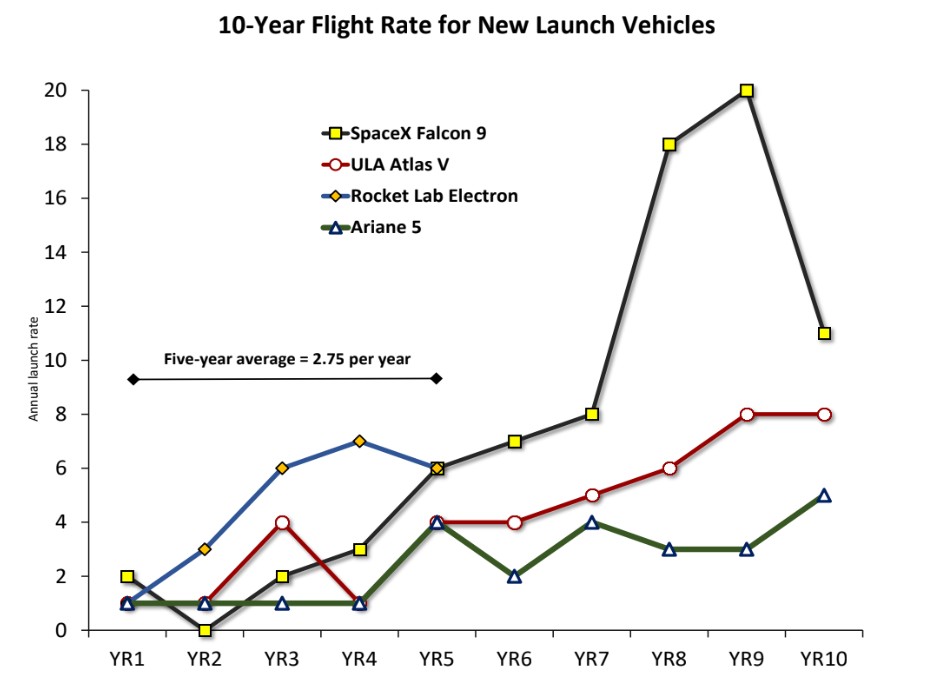

According to this analysis, some recent rockets launched an average of 2.75 times a year during their first five years.

Quilty Space

After certification, United Launch Alliance can begin to fly military missions. However, it is one thing to build one or two rockets, it is quite another to build them at scale. The company’s goal is to reach a cadence of two Vulcan launches a month by the end of 2025. In his letter, Calvelli mentioned that United Launch Alliance has averaged fewer than six launches a year during the last five years. This indicates a concern that such a goal may be unreasonable.

“History shows that new rockets struggle to scale their launch cadence in their early years,” Caleb Henry, director of research at Quilty Space, told Ars. “Based on the number of missions the Department of Defense requires of ULA between now and 2027, precedent says Calvelli’s concerns are justified.”