“In simple terms, we use genetic tools that allow us to inject mice with a drug that artificially makes astrocytes express some other gene or protein of interest when they become active,” says Wookbong Kwon, a biotechnologist at Baylor College and co-author of the study.

Those proteins of interest were mainly fluorescent proteins that make cells fluoresce bright red. This way, the team could spot the astrocytes in mouse brains that became active during learning scenarios. Once the tagging system was in place, Williamson and his colleagues gave their mice a little scare.

“It’s called fear conditioning, and it’s a really simple idea. You take a mouse, put it into a new box, one it’s never seen before. While the mouse explores this new box, we just apply a series of electrical shocks through the floor,” Williamson explains. A mouse treated this way remembers this as an unpleasant experience and associates it with contextual cues like the box’s appearance, the smells and sounds present, and so on.

The tagging system lit up all astrocytes that expressed the c-Fos gene in response to fear conditioning. Williamson’s team inferred that this is where the memory is stored in the mouse’s brain. Knowing that, they could move on to the next question, which was if and how astrocytes and engram neurons interacted during this process.

Modulating engram neurons

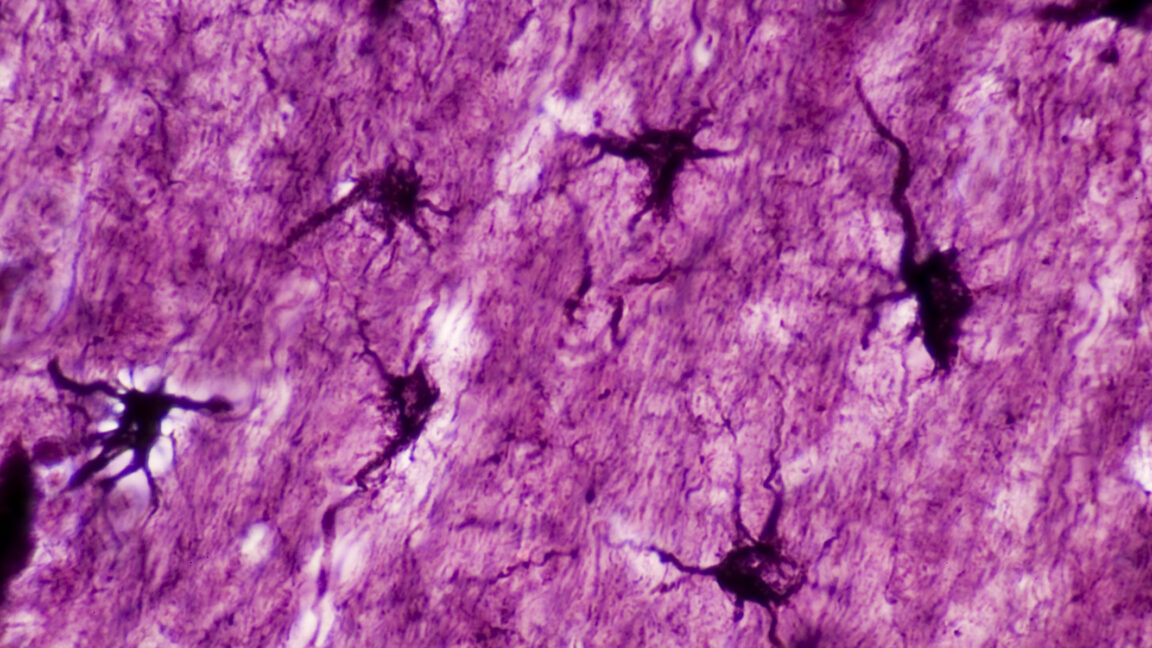

“Astrocytes are really bushy,” Williamson says. They have a complex morphology with lots and lots of micro or nanoscale processes that infiltrate the area surrounding them. A single astrocyte can contact roughly 100,000 synapses, and not all of them will be involved in learning events. So the team looked for correlations between astrocytes activated during memory formation and the neurons that were tagged at the same time.