CNR – Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche

Historical accounts vary about how the Greek philosopher Plato died: in bed while listening to a young woman playing the flute; at a wedding feast; or peacefully in his sleep. But the few surviving texts from that period indicate that the philosopher was buried somewhere in the garden of the Academy he founded in Athens. The garden was quite large, but archaeologists have now deciphered a charred ancient papyrus scroll recovered from the ruins of Herculaneum, indicating a more precise burial location: in a private area near a sacred shrine to the Muses, according to Constanza Millani, director of the Institute of Heritage Science at Italy’s National Research Council.

As previously reported, the ancient Roman resort town Pompeii wasn’t the only city destroyed in the catastrophic 79 AD eruption of Mount Vesuvius. Several other cities in the area, including the wealthy enclave of Herculaneum, were fried by clouds of hot gas called pyroclastic pulses and flows. But still, some remnants of Roman wealth survived. One palatial residence in Herculaneum—believed to have once belonged to a man named Piso—contained hundreds of priceless written scrolls made from papyrus, singed into carbon by volcanic gas.

The scrolls stayed buried under volcanic mud until they were excavated in the 1700s from a single room that archaeologists believe held the personal working library of an Epicurean philosopher named Philodemus. There may be even more scrolls still buried on the as-yet-unexcavated lower floors of the villa. The few opened fragments helped scholars identify various Greek philosophical texts, including On Nature by Epicurus and several by Philodemus himself, as well as a handful of Latin works. But the more than 600 rolled-up scrolls were so fragile that it was long believed they would never be readable, since even touching them could cause them to crumble.

Scientists have brought all manner of cutting-edge tools to bear on deciphering badly damaged ancient texts like the Herculaneum scrolls. For instance, in 2019, German scientists used a combination of physics techniques (synchrotron radiation, infrared spectroscopy, and X-ray fluorescence) to virtually “unfold” an ancient Egyptian papyrus.

Brent Searles’ lab at the University of Kentucky has been working on deciphering the Herculaneum scrolls for many years. He employs a different method of “virtually unrolling” damaged scrolls, using digital scanning with micro-computed tomography—a noninvasive technique often used for cancer imaging—with segmentation to digitally create pages, augmented with texturing and flattening techniques. Then they developed software (Volume Cartography) to virtually unroll the scroll.

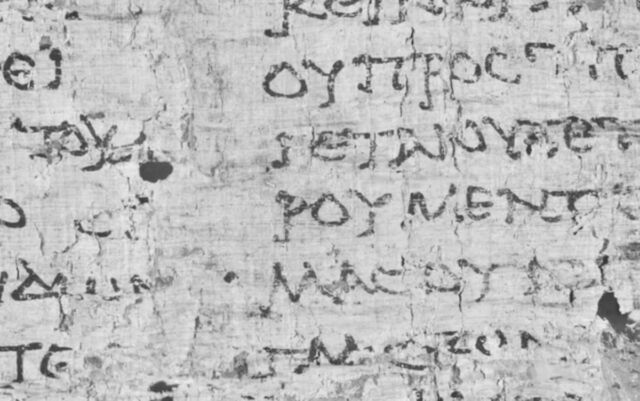

The older Herculaneum scrolls were written with carbon-based ink (charcoal and water), so one would not get the same fluorescing in the CT scans, but the scans can still capture minute textural differences indicating those areas of papyrus that contained ink compared to the blank areas, and it’s possible to train an artificial neural network to do just that.

D.P. Pavone

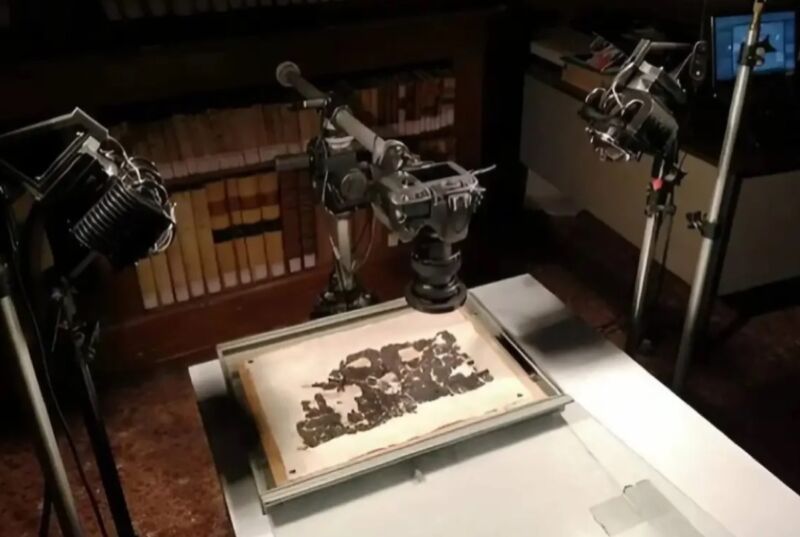

This latest work is under the auspices of the “GreekSchools” project, funded by the European Research Council, which began three years ago and will continue through 2026. This time around, scholars have used infrared, ultraviolet optical imaging, thermal imaging, tomography, and digital optical microscopy as a kind of “bionic eye” to examine Philodemus’ History of the Academy scroll, which was also written in carbon-based ink. Nonetheless, they were able to extract over 1,000 words, approximately 30 percent of the scroll’s text, revealing new details about Plato’s life as well as his place of burial.

Most notably, the historical account of Plato being sold into slavery in his later years after running afoul of the tyrannical Dionysius is usually pegged to around 387 BCE. According to the newly deciphered Philodemus text, however, Plato’s enslavement may have occurred as early as 404 BCE or shortly after the death of Socrates in 399 BCE.

“Compared to previous editions, there is now an almost radically changed text, which implies a series of new and concrete facts about various academic philosophers,” Graziano Ranocchia, lead researcher on the project, said. “Through the new edition and its contextualization, scholars have arrived at unexpected interdisciplinary deductions for ancient philosophy, Greek biography and literature, and the history of the book.”

Other deciphering efforts are also still underway. For instance, last fall we reported on the use of machine learning to decipher the first letters from a previously unreadable ancient scroll found in an ancient Roman villa at Herculaneum—part of the 2023 Vesuvius Challenge. And earlier this year tech entrepreneur and challenge co-founder Nat Friedman announced via X (formerly Twitter) that they had awarded the grand prize of $700,000 for producing the first readable text.

When the Vesuvius Challenge co-founders started the challenge, they thought there was less than a 30 percent chance of success within the year since, at the time, no one had been able to read actual letters inside of a scroll. However, the crowdsourcing approach proved wildly successful. That said, it’s still just 5 percent of a single scroll.

So there is a new challenge for 2024: $100,000 for the first entry that can read 90 percent of the four scrolls scanned thus far. The primary goal is to perfect the auto-segmentation process since doing so manually is both time-consuming and expensive (more than $100 per square centimeter). This will lay the foundation for one day being able to scan and read all 800 scrolls discovered so far, as well as any additional scrolls that are unearthed should the remaining levels of the villa finally be excavated.