Study shows advanced imaging, expert review improve diagnosis of encephaloceles

The sound of a basketball bouncing, the squeak of shoes on a fast break, the swish of the net — basketball has been a constant for Parker Shanks — from youth leagues to high school and college teams, to pickup games at his local gym.

One day on the court in 2022, a seizure dropped 6-foot-8-inch Parker to the floor.

Watch: Back to basketball after surgery

Journalists: Broadcast-quality video (2:30) is in the downloads at the end of this post. Please courtesy: “Mayo Clinic News Network.” Read the script.

“The next thing I know, I’m lying down in the middle of the basketball court, and there’s a stretcher coming to pick me up and (they) drive me to the ER,” recalls Parker, now 24. “That’s when it really hits that, no, we’re not just done and out of this. Something really is going on.”

That something turned out to be a skull abnormality called an encephalocele (en-SEFF-ah-loh-seal), which caused Parker to have seizures.

Today, three years after his journey with epilepsy started, Parker’s seizures are in control, and he’s enjoying new responsibilities at his job and shooting hoops again.

If sharing his experience could help someone else find answers, Parker is all in, especially as he’s learned that encephaloceles are becoming more recognized as a cause of seizures. “If talking about this can help someone else, absolutely, without question,” Parker says.

Re-review of imaging finds encephaloceles that cause seizures

There are distinct types and severities of encephaloceles. Some are present at birth and can be large. One in every 10,500 babies is born with this type of rare, large encephalocele, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Other encephaloceles, like Parker’s, occur after birth when the bony plates of the skull do not fuse together completely during growth, explains Dr. Jeffrey Britton, a Mayo Clinic neurologist. This allows part of the brain to push through small gaps in the skull, producing an encephalocele. These small encephaloceles are typically under a half-inch in size. As a result, they are difficult to detect on MRI scans.

“Their relevance as a seizure cause has been increasingly appreciated in recent years,” Dr. Britton says. “The ability to visualize them has increased with technological advances, and our ability to recognize them as clinicians and radiologists is improving.”

In a retrospective study analyzing encephalocele cases in patients with epilepsy who underwent surgery from 2008 to 2020, Mayo Clinic researchers reported that the encephaloceles were initially overlooked on MRI in 31 of 34, or 91%, of cases. Expert re-review of patients’ imaging as part of Mayo Clinic’s weekly multidisciplinary epilepsy surgery conference has significantly improved identification of encephaloceles, says Dr. Kelsey Smith, a Mayo Clinic neurologist and first author of the study published November 2023 in Epilepsy & Behavior.

Drs. Smith and Britton are part of the integrated team of Mayo Clinic neurologists, neuroradiologists, neuropsychologists and neurosurgeons that meets weekly to discuss patient cases and recommend individualized, innovative treatment plans. They review patients’ medical histories and look for brain image irregularities that may indicate an encephalocele.

“When you have someone with drug-resistant epilepsy, if you can find a lesion that’s the cause of their epilepsy, it really changes the possibilities for the patient’s treatment,” Dr. Smith says. “That is why looking at imaging closely for abnormalities like encephaloceles is very important.”

Since the Mayo study ended in 2020, the team has found roughly 20 encephaloceles in additional patients with epilepsy, Parker among them. Parker has a scar — shaped like a question mark over his left temple — to prove it.

Seizures triggered by sudden change in brain physiology

In May 2021, Parker was a 21-year-old junior at the University of Wisconsin-Stout in Menomonie when he first had a seizure. “I’m hanging out with a buddy, and suddenly he tells me he called an ambulance. He said, ‘Dude, you just had a seizure,'” Parker recalls.

With no prior history of seizures, medication might not be started after one seizure. But a month later, Parker had a second. He underwent testing at Mayo Clinic Health System in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, and was prescribed anti-seizure medication.

For over a year, Parker was seizure-free. But after his seizure that day on the basketball court, epilepsy began to rule Parker’s life. Following standard treatment, Parker’s medication dosage was increased, and another medication was tried. His seizures would be under control and then return.

“It got to a scarily regular basis, where I was having the grand mal seizures about monthly, and then I was having the focal ‘zone out’ seizures at least weekly,” says Parker, despite taking medication diligently.

Dr. Britton describes epilepsy as a temporary electrical short circuit or an electrical storm in the brain. “The one thing that different types of seizures have in common is that they result from a sudden surge in the excitability of the brain,” he says.

Seizures create ‘shadow in the back of my head’

Epilepsy is common. Worldwide, it’s estimated more than 50 million people of all ages have epilepsy, according to the World Health Organization. In the U.S., more than 3 million people have epilepsy, according to the CDC. For a third of them, like Parker, medications don’t control their seizures.

Dangerous complications can result from seizures — falling, drowning, motor vehicle accidents, dealing with side effects of medications and the mental stress of illness, and even sudden, unexpected death.

Parker fell and hit his head several times during seizures. A woman discovered him on the sidewalk near his office. She called 911 and his parents, thanks to an identification bracelet Parker wears.

Once, after being seizure-free for a few months, Parker crashed his car during a seizure. He shudders to think what would have happened if anyone had been seriously hurt in the accident.

Parker stopped driving. He curtailed his social activities. At work in Eau Claire, he was glad for a desk job — on carpeting — in case he fell.

“I’m not going outside and doing anything else because I just have that shadow in the back of my head,” says Parker, offering thanks to his family and friends who gave him rides and support during some frustrating and frightening months.

Finding the culprit behind Parker’s seizures

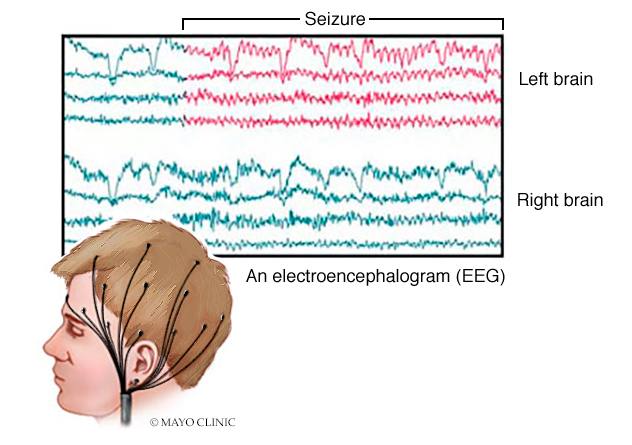

Parker was hospitalized in Eau Claire to monitor his seizures using an electroencephalogram (EEG), a test that measures electrical activity in the brain using small, metal electrode discs attached to the scalp. Parker’s seizures were found to arise from his temporal lobe on the left side of his brain.

At Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, that EEG information and Parker’s medical history suggested the temporal lobe was the source of his seizures. Identifying the underlying encephalocele involved the use of advanced imaging:

- Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scan, which indicates how glucose is fueling parts of the brain. Parker’s scan showed a specific area of abnormal glucose uptake in the front tip of the left temporal lobe.

- 3D-rendering CT scan, which can enhance visualization of the skull base. Parker’s scan revealed a defect in the floor of the left middle of the skull base and the corresponding encephalocele.

- 7T MRI scan, which can reveal subtle brain differences, and is used when the team is highly suspicious that a lesion is present but conventional imaging has not helped.

“The location of Parker’s encephalocele had complex, curved anatomy with brain, bone and air close together,” says Dr. Karl Krecke, a Mayo Clinic neuroradiologist, describing Parker’s roughly half-inch encephalocele.

“When each of these imaging data pieces line up, we feel confident that we have found the culprit, and we can consider options to treat the patient’s problem.”

Seizure surgery date is ‘my new birthday’

Dr. Britton delivered the news to Parker and his parents that an encephalocele likely was causing his seizures, and surgical repair was an option. “It’s really a privilege to be in a position where you can be a part of a process that brings clear benefits to an individual patient,” Dr. Britton says. “It’s what keeps you going.”

Dr. Jamie Van Gompel, a Mayo Clinic neurosurgeon, soon met with Parker and his family to discuss the risks and benefits of surgery. Research by the Mayo team has shown that a more limited surgery is best for a temporal encephalocele on the left side of the brain, which controls speech and memory.

“We went to surgery and were able to remove a small part of the brain tissue that was hurt by the encephalocele,” Dr. Van Gompel says. “Parker was amazing, out of the hospital quickly and back to doing what makes Parker, Parker.”

After dealing with fear and anxiety caused by his seizures, Parker had a special message for his operating room team before he went under anesthesia for his October 2023 surgery. As he lay on the operating table, he asked to make an announcement before his procedure started.

“Me and my family have gone through the greatest amount of trauma and stress for something that was out of nowhere,” Parker recalls telling the team. “And knowing that you guys are the best possibility for me to get my life back, I’m seeing this as my new birthday. So, thank you.”

After a recent checkup with Dr. Britton, Parker reiterates the sentiment. “I can’t thank them enough. I don’t know how else to put it. I’ve got my life back.”