Matthew Dominick/NASA

Officially, of course, the Atlantic hurricane season begins on June 1, But most years, the tropics remain fairly sleepy for the first month or two, allowing coastal residents to ease into the season.

Yes, a tropical storm might form here or a modest hurricane there. But the really big and powerful hurricanes, which develop from tropical waves in the central Atlantic and roar into the Caribbean Sea, do not spin up until August or September when seas reach their peak temperatures.

Not so this year, in which the Atlantic Ocean is boiling already. The seas in the main development region of the Atlantic have already reached temperatures not normally seen until August or September. This has led to the rapid intensification of Hurricane Beryl, which crashed through the Windward Islands on Monday and is now traversing the Caribbean Sea toward Jamaica.

Beryl is, to put it mildly, a freak storm.

It intensified on Monday night into a Category 5 hurricane, with sustained winds of 165 mph. Like other meteorologists, I had to check my calendar to verify that it really just was the first day of July. Remember, we’re still in the traditionally “sleepy” part of hurricane season. Prior to Beryl, in more than a century of hurricane records, the earliest a Category 5 hurricane has ever developed in the Atlantic was July 16. That was Hurricane Emily, in 2005, the notorious hurricane season that delivered Katrina to New Orleans about a month later.

Getting stronger, faster

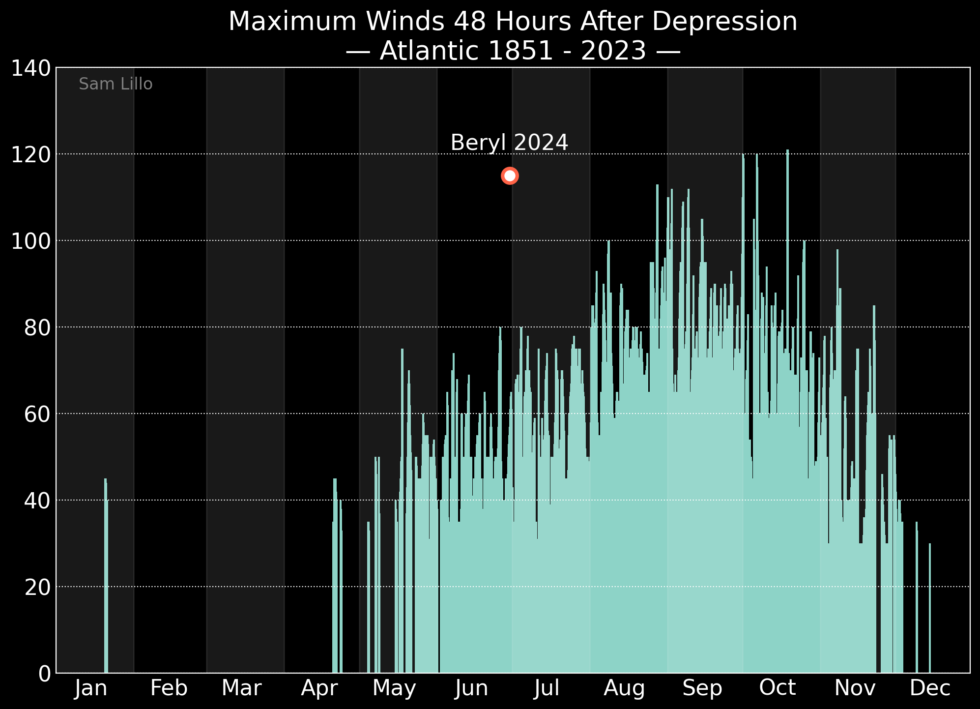

The rapid transformation of Beryl from a tropical depression into a major hurricane in 48 hours would have been super impressive for an Atlantic storm in September. Although not quite record-setting for the peak of the Atlantic hurricane season, this kind of intensification is absolutely unheard of for June or July. This graphic, from meteorologist Sam Lillo, puts the unprecedented nature of Beryl’s rapid intensification into perspective.

Writing about the strengthening of Beryl on Sunday, University of Miami atmospheric scientist Brian McNoldy summed up how meteorologists feel observing such a storm so early in the season. “It’s hard to communicate how unbelievable this is,” he wrote. “With La Niña on the way and the ocean temperatures already looking like the second week of September, this is precisely the type of outlier event that people have been talking about for months heading into this season. When you have an unprecedented favorable environment, you’re bound to see unprecedented tropical cyclone activity.”

The superlatives for Beryl don’t stop there. According to seasonal hurricane forecaster Phil Klotzbach, Beryl formed farther east in the Atlantic than any previous hurricane on record, beating even the 1933 season (another notorious outlier in terms of activity). That’s another sign that the main development region of the Atlantic tropics is heating up way ahead of schedule this year.

Fortunately, Beryl is now likely at its peak intensity. Over the next 24 hours, it should begin to encounter higher levels of wind shear, which is kryptonite for the organization of a tropical cyclone. The hurricane should also start to run into some drier air.

However, Beryl will still probably be a major hurricane when it strikes or passes just south of the Caribbean island of Jamaica on Wednesday. And it will probably remain at hurricane strength when it nears Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula late on Thursday or Friday morning. After this, the storm should move into the southern Gulf of Mexico. There, it is unlikely to regain hurricane strength, but it could bring some rain showers to Mexico and Texas. We’ll have to see.

The climate changes, storms get stronger

The point here is not really to discuss the threat of Beryl to the United States, which at this point seems in the modest-to-minimal range. Rather, it’s the implications of Beryl both for the rest of the Atlantic season and as a harbinger for what to expect from the tropics in a world where we see warmer seas on the regular.

For this year, forecasters have been consistently predicting a hyperactive season due to the combination of roasting sea surface temperatures and the onset of La Niña during the critical months of August, September, and October. That forecast seems to be right on track and will be of concern to all coastal residents in the United States, Mexico, and the Caribbean islands. If Beryl is smashing records from 2005 and 1933 already, we’re in “this is fine” territory.

Longer term, the implications are sobering for hurricanes in a world modified by climate change. The emerging consensus from scientists has been that there will be a 1 to 10 percent increase in tropical cyclone intensities and that the proportion of major hurricanes will increase. But even in such a world, Beryl would be an outlier. That we’re already seeing superstorms develop in late June and early July should concern everyone everywhere.