Electricity supply is becoming the latest chokepoint to threaten the growth of artificial intelligence, according to leading tech industry chiefs, as power-hungry data centers add to the strain on grids around the world.

Billionaire Elon Musk said this month that while the development of AI had been “chip constrained” last year, the latest bottleneck to the cutting-edge technology was “electricity supply.” Those comments followed a warning by Amazon chief Andy Jassy this year that there was “not enough energy right now” to run new generative AI services.

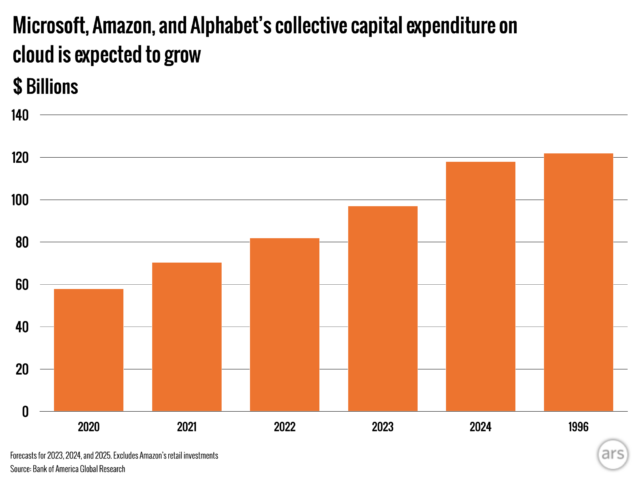

Amazon, Microsoft, and Google parent Alphabet are investing billions of dollars in computing infrastructure as they seek to build out their AI capabilities, including in data centers that typically take several years to plan and construct.

But some of the most popular places for building the facilities, such as northern Virginia, are facing capacity constraints which, in turn, are driving a search for suitable sites in growing data center markets globally.

“Demand for data centers has always been there, but it’s never been like this,” said Pankaj Sharma, executive vice president at Schneider Electric’s data center division.

At present, “we probably don’t have enough capacity available” to run all the facilities that will be required globally by 2030, said Sharma, whose unit is working with chipmaker Nvidia to design centers optimized for AI workloads.

“One of the limitations of deploying [chips] in the new AI economy is going to be … where do we build the data centers and how do we get the power,” said Daniel Golding, chief technology officer at Appleby Strategy Group and a former data center executive at Google. “At some point the reality of the [electricity] grid is going to get in the way of AI.”

Ars Technica

The power supply issue has also fuelled concerns about the latest technology boom’s environmental impact.

Countries worldwide need to meet renewable energy commitments and electrify sectors such as transportation in response to accelerating climate change. To support these changes, many nations will need to reform their electricity grids, according to analysts.

The demands on the power grid are “top of mind” for Amazon, said the company’s sustainability chief, Kara Hurst, adding that she was “regularly in conversation” with US officials about the issue.

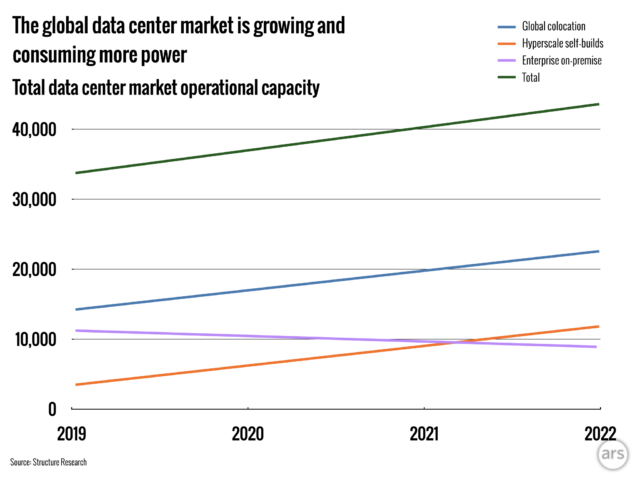

Data centers—industrial buildings, often covering large areas of land, that house the physical components underpinning computer systems, such as cabling, chips and servers—are part of the backbone of computing.

Research group Dgtl Infra has estimated that global data center capital expenditure will surpass $225 billion in 2024. Nvidia’s chief executive Jensen Huang said this year that $1 trillion worth of data centers would need to be built in the next several years to support generative AI, which is power intensive and involves the processing of enormous volumes of information.

Such growth would require huge amounts of electricity, even if systems become more efficient. According to the International Energy Agency, the electricity consumed by data centers globally will more than double by 2026 to more than 1,000 terawatt hours, an amount roughly equivalent to what Japan consumes annually.

“Updated regulations and technological improvements, including on efficiency, will be crucial to moderate the surge in energy consumption from data centers,” the IEA said this year.

US data center electricity consumption is expected to grow from 4 percent to 6 percent of total demand by 2026, while the AI industry is forecast to expand “exponentially” and consume at least 10 times its 2023 demand by 2026, said the IEA.

Ars Technica

Even before the generative AI boom, some major markets were struggling to keep up with demand. It can take years for new renewable energy projects such as wind farms to gain regulatory approval and be connected to the grid. There is also a need in some places to build new transmission lines that carry electricity from one point to another.

In northern Virginia, the world’s largest data center hub, power provider Dominion Energy paused new data center connections in 2022 while it analyzed how to deal with the jump in demand, including by upgrading parts of its network.

In October, the company said in filings to a Virginia regulator that it was experiencing “significant load growth due to data center development” and that growing power demands presented a “challenge.”

In response to the demand, authorities in jurisdictions including Ireland and the Netherlands have sought to limit new data center developments, while Singapore recently lifted a moratorium.

Developers are looking to build sites in growing areas such as the US states of Ohio and Texas, regions of Italy and eastern Europe, Malaysia and India, according to analysts.

Finding appropriate sites can be challenging, with power just one factor to consider among others such as the availability of large volumes of water to cool data centers.

“For every 50 sites I look at, maybe two get to the point where they may be developed,” said Appleby Strategy’s Golding. “Folks are sifting through large numbers of properties.”

The concerns have driven interest among data center developers in options such as onsite power generation and nuclear energy, with Microsoft this year hiring a director of “nuclear development acceleration.”

© 2024 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Not to be redistributed, copied, or modified in any way.